3 Reputation-based Lotteries

At the heart of our construction is a lottery that chooses a (sublinear) set of parties

according to their reputation.

To demonstrate the idea, let us first consider two extreme scenarios: Scenario 1: No reputation party  i has

Ri > 0.5. Scenario 2: All reputation parties

i has

Ri > 0.5. Scenario 2: All reputation parties  i have (independent) reputation Ri > 0.5 + ϵ for a constant ϵ, e.g,.

Ri > 0.51.

i have (independent) reputation Ri > 0.5 + ϵ for a constant ϵ, e.g,.

Ri > 0.51.

In Scenario 1, one can prove that users cannot use the recommendation of the reputation parties to agree on a sequence of transactions. Roughly, the reason is that with good probability, the majority of the reputation parties might be dishonest and try to split the network of users, so that they accept conflicting transaction sequences. In Scenario 2, on the other hand, the situation is different. Here, by choosing a polylogarithmic random committee we can guarantee (except with negligible probability)8 that the majority of those parties will be honest (recall that we assume independent reputations), and we can therefore employ a consensus protocol to achieve agreement on each transaction (block).

Definition 1. For a reputation system Rep for parties from a reputation set  ,

a (possibly probabilistic) algorithm A for sampling a subset of parties from

,

a (possibly probabilistic) algorithm A for sampling a subset of parties from  , and

an Rep-adversary

, and

an Rep-adversary  , we say that Rep is (ϵ,A)-feasible for

, we say that Rep is (ϵ,A)-feasible for  if, with overwhelming

probability,9

A outputs a set of parties such that at most a 1∕2 - ϵ fraction of these parties is corrupted by

if, with overwhelming

probability,9

A outputs a set of parties such that at most a 1∕2 - ϵ fraction of these parties is corrupted by  .

.

In the above definition, the corrupted parties are chosen according to Rep from the entire reputation-party set  ,

and independently of the coins of A. (Indeed, otherwise it would be trivial to corrupt a majority.)

,

and independently of the coins of A. (Indeed, otherwise it would be trivial to corrupt a majority.)

Definition 2. We say that a reputation system is ϵ-feasible for Rep-adversary  , if there exists a

probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) sampling algorithm A such that Rep is (ϵ,A)-feasible for

, if there exists a

probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) sampling algorithm A such that Rep is (ϵ,A)-feasible for  .

.

It is easy to verify that to maximize the (expected) number of honest parties in the

committee it suffices to

always choose the parties with the highest reputation. In fact, [13] generalized this to arbitrary correlation-free

reputation systems by proving that for any ϵ-feasible reputation system Rep (i.e., for any Rep-adversary  ) the

algorithm which orders that parties according to their reputation chooses sufficiently many (see. [13]) parties

with the highest reputation induces a set which has honest majority. We denote this algorithm by

Amax.

) the

algorithm which orders that parties according to their reputation chooses sufficiently many (see. [13]) parties

with the highest reputation induces a set which has honest majority. We denote this algorithm by

Amax.

Lemma 1 ([13]). A correlation-free reputation system is ϵ-feasible for a Rep-adversary  if and only if

it is (ϵ,Amax)-feasible for

if and only if

it is (ϵ,Amax)-feasible for  .

.

As discussed in the introduction, despite yielding a maximally safe lottery, Amax has issues with fairness which renders it suboptimal for use in a blockchain ledger protocol. In the following we introduce an appropriate notion of reputation-fairness for lotteries and an algorithm for achieving it.

3.1 PoR-Fairness

As a warm up, let us consider a simple case, where all reputations parties can be

partitioned in two subsets:  1

consisting of parties with reputation at least 0.76, and

1

consisting of parties with reputation at least 0.76, and  2 consisting of parties with reputation between 0.51 and

0.75. Let |

2 consisting of parties with reputation between 0.51 and

0.75. Let | 1| = α1 and |

1| = α1 and | 2| = α2. We want to sample a small (sublinear in |

2| = α2. We want to sample a small (sublinear in | | = α1 + α2) number y of parties in

total.

| = α1 + α2) number y of parties in

total.

Recall that we want to give every reputation party a chance (to be part of the committee) while

ensuring that, the higher the reputation, the better his relative chances. A first attempt would be to first

sample a set where each party  i is sampled according to his reputation (i.e., with probability Ri)

and then reduce the size of the sampled set by randomly picking the desired number of parties. This

seemingly natural idea suffers from the fact that if there are many parties with low reputation—this is not

the case in our above example where everyone has reputation at least 0.51, but it might be the case

in reality—then it will not yield an honest majority committee even when the reputation system is

feasible.

i is sampled according to his reputation (i.e., with probability Ri)

and then reduce the size of the sampled set by randomly picking the desired number of parties. This

seemingly natural idea suffers from the fact that if there are many parties with low reputation—this is not

the case in our above example where everyone has reputation at least 0.51, but it might be the case

in reality—then it will not yield an honest majority committee even when the reputation system is

feasible.

A second attempt is the following. Observe that per our specification of the above tiers, the parties

in  1 are

about twice more likely to be honest than parties in

1 are

about twice more likely to be honest than parties in  2. Hence we can try to devise a lottery which selects (on

expectation) twice as many parties from

2. Hence we can try to devise a lottery which selects (on

expectation) twice as many parties from  1 as the number of parties selected from

1 as the number of parties selected from  2. This will make the final set

sufficiently biased towards high reputations (which can ensure honest majorities) but has the following side-effect:

The chances of a party being selected diminish with the number of parties in his reputation tier. This effectively

penalizes large sets of high-reputation parties; but formation of such sets should be a desideratum for a blockchain

protocol. To avoid this situation we tune our goals to require that when the higher-reputation set |

2. This will make the final set

sufficiently biased towards high reputations (which can ensure honest majorities) but has the following side-effect:

The chances of a party being selected diminish with the number of parties in his reputation tier. This effectively

penalizes large sets of high-reputation parties; but formation of such sets should be a desideratum for a blockchain

protocol. To avoid this situation we tune our goals to require that when the higher-reputation set | 1| is much larger

than |

1| is much larger

than | 2|, then we want to start shifting the selection towards

2|, then we want to start shifting the selection towards  1. This leads to the following informal fairness

goal:

1. This leads to the following informal fairness

goal:

Goal (informal): We want to randomly select x1 parties from  1 and x2 parties from

1 and x2 parties from  2 so that:

2 so that:

- 1.

- x1 + x2 = y

- 2.

- x1 = 2max{1,

}x2 (representation fairness)

}x2 (representation fairness)

- 3.

- For each i ∈{1,2} : No party in

i has significantly lower probability of getting picked than other parties

in

i has significantly lower probability of getting picked than other parties

in  i (non-discrimination), but parties in

i (non-discrimination), but parties in  1 are twice as likely to be selected as parties in

1 are twice as likely to be selected as parties in  2 (selection

fairness).

2 (selection

fairness).

Assuming α1 and α2 are sufficiently large, the above goal can be achieved by the following sampler:

For

appropriately chosen numbers ℓ1 and ℓ2 ≥ 0 with ℓ1 + ℓ2 = y, sample ℓ1 parties from  1, and then sample ℓ2 parties

from

1, and then sample ℓ2 parties

from  1 ∪

1 ∪ 2 (where if you sample a party from

2 (where if you sample a party from  1 twice, replace him with a random, upsampled party from

1 twice, replace him with a random, upsampled party from

1). As it will become clear in the following general analysis, by carefully

choosing ℓ1 and ℓ2 we can

ensure that the conditions of the above goal are met. For the interested reader, we analyze the above

lottery in Appendix

A.1

. Although this is a special case of the general

lottery which follows, going over

that simpler analysis might be helpful to a reader, who wishes to ease into our techniques and design

choices.

1). As it will become clear in the following general analysis, by carefully

choosing ℓ1 and ℓ2 we can

ensure that the conditions of the above goal are met. For the interested reader, we analyze the above

lottery in Appendix

A.1

. Although this is a special case of the general

lottery which follows, going over

that simpler analysis might be helpful to a reader, who wishes to ease into our techniques and design

choices.

Our PoR-Fairness Definition and Lottery

We next discuss how to turn the above informal fairness goals into a formal definition,

and generalize the

above lottery mechanism to handle more than two reputation tiers and to allow for arbitrary

reputations. To this direction we partition, as in the simple example, the reputations in m = O(1)

tiers10 as

follows: For a given small δ > 0, the first tier includes parties with reputation between  + δ and 1, the second

tier includes parties with reputation between

+ δ and 1, the second

tier includes parties with reputation between  + δ and

+ δ and  + δ, and so on. Parties with reputation 0 are

ignored.11

We refer to the above partitioning of the reputations as an m-tier partition.

+ δ, and so on. Parties with reputation 0 are

ignored.11

We refer to the above partitioning of the reputations as an m-tier partition.

The main differences of the generalized reputation-fairness notion from the above informal goal, is that (1) we parameterize the relation between the representation of different ties by a parameter c (in the above informal goal c = 2) and (2) we do not only require an appropriate relation on the expectations of the numbers of parties from the different tiers but require that these numbers are concentrated around numbers that satisfy this relation. The formal reputation fairness definition follows.

Definition 3. Let  1,…,

1,…, m be a partition of the reputation-party set

m be a partition of the reputation-party set  into m tiers as above (where the

parties in

into m tiers as above (where the

parties in  1 have the highest reputation) and let L be a lottery which selects xi parties from each

1 have the highest reputation) and let L be a lottery which selects xi parties from each  i. For

some c ≥ 1, we say that L is c-reputation-fair, or simply, c-fair if it satisfies the following properties:

i. For

some c ≥ 1, we say that L is c-reputation-fair, or simply, c-fair if it satisfies the following properties:

- 1.

-

(c-Representation Fairness): For j = 1,…,m, let cj = max{c,c ⋅

}. Then L is c-fair if for each

j ∈{0,…,m - 1} and for every constant ϵ ∈ (0,c):

}. Then L is c-fair if for each

j ∈{0,…,m - 1} and for every constant ϵ ∈ (0,c):

![Pr [(cj - ϵ)xj+1 ≤ xj ≤ (cj + ϵ)xj+1] ≥ 1- μ(k),](main56x.png)

- 2.

-

(c-Selection Fairness): For any pj ∈ ∪i=1m

i, let Memberj denote the indicator (binary) random

variable which is 1 if pj is selected by the lottery and 0 otherwise. The L is c-selection-fair if for any

i ∈{1,…,m - 1}, for any pair (

i, let Memberj denote the indicator (binary) random

variable which is 1 if pj is selected by the lottery and 0 otherwise. The L is c-selection-fair if for any

i ∈{1,…,m - 1}, for any pair ( i1,

i1, i2) ∈

i2) ∈ i ×

i × i+1, and any constant c′ < c:

i+1, and any constant c′ < c:

![Pr[Memberi1-=-1]≥ c′ - μ(k)

Pr[Memberi2 = 1]](main62x.png)

- 3.

-

(Non-Discrimination): Let Memberi defined as above. The L is non-discriminatory if for any

i1,

i1, i2

in the same

i2

in the same  i:

i:

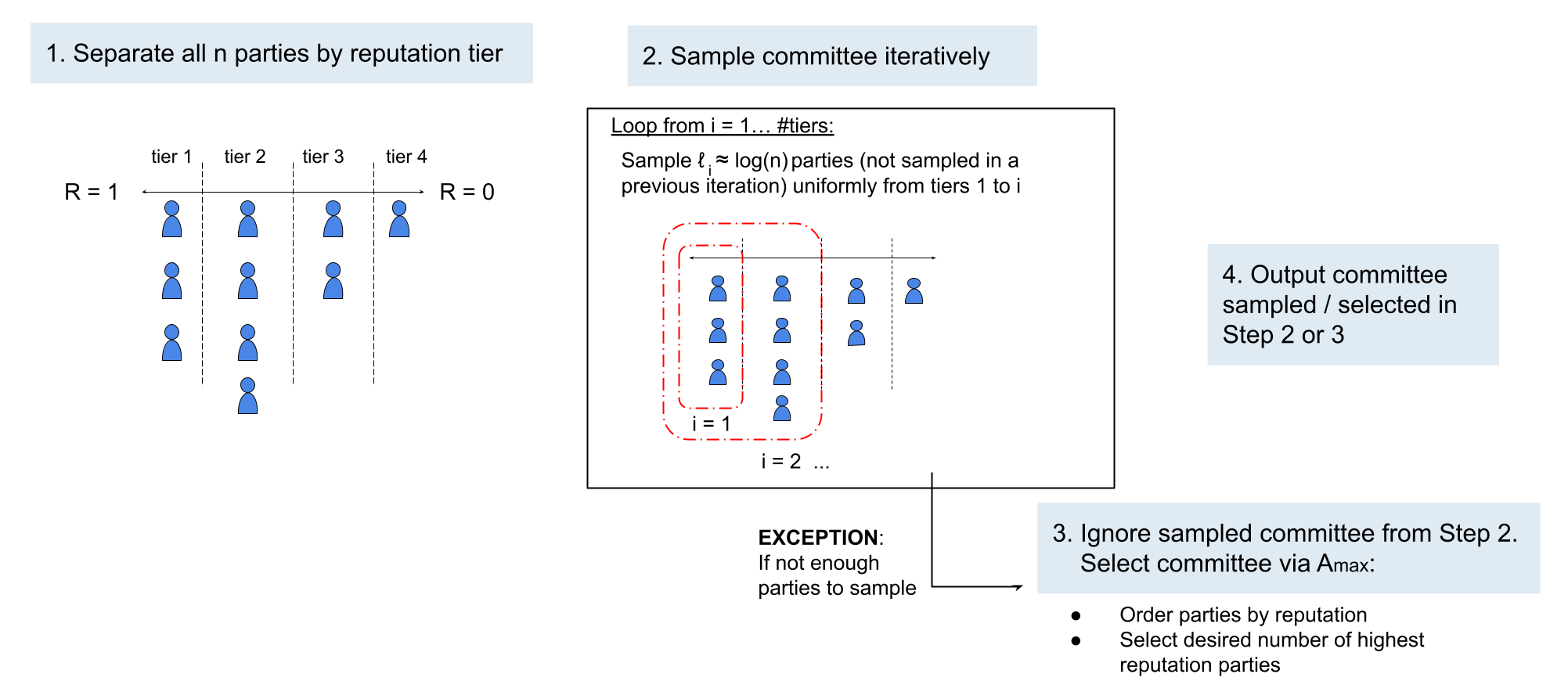

A high level description of the lottery is given in Fig.

5

. Informally, lottery for the m-tier case is similar in spirit

to the two-tier case: First we sample a number of ℓ1 parties from the highest reputation set  1, then we sample ℓ2

parties from the union of second-highest and the highest

1, then we sample ℓ2

parties from the union of second-highest and the highest  1 ∪

1 ∪ 2, then we sample ℓ3 parties from the union of

the three highest reputation tiers

2, then we sample ℓ3 parties from the union of

the three highest reputation tiers  1 ∪

1 ∪ 2 ∪

2 ∪ 3, and so on. As we prove, the values ℓ1,ℓ2,ℓ3 etc. can

be carefully chosen so that the above fairness goal is reached whenever there are sufficiently many

parties in the different tiers. We next detail our generalized sampling mechanism and prove its security

properties.

3, and so on. As we prove, the values ℓ1,ℓ2,ℓ3 etc. can

be carefully chosen so that the above fairness goal is reached whenever there are sufficiently many

parties in the different tiers. We next detail our generalized sampling mechanism and prove its security

properties.

We start by describing two standard methods for sampling a size-t subset of

a party set  —where each party P ∈

—where each party P ∈  is associated with a unique identifier

pid12—which

will both be utilized in our fair sampling algorithm. Intuitively, the first sampler samples the set with

replacement and

the second without. The first method, denoted by Rand, takes as input/parameters the set

is associated with a unique identifier

pid12—which

will both be utilized in our fair sampling algorithm. Intuitively, the first sampler samples the set with

replacement and

the second without. The first method, denoted by Rand, takes as input/parameters the set  , the size of the target set

t—where naturally t < |

, the size of the target set

t—where naturally t < | |—and a nonce r. It also makes use of a hash function h which we will assume behaves as a random

oracle.13

In order to sample the set, for each party with ID pid, the sampler evaluates the random oracle on input (pid,r) and

if the output has more than log

|—and a nonce r. It also makes use of a hash function h which we will assume behaves as a random

oracle.13

In order to sample the set, for each party with ID pid, the sampler evaluates the random oracle on input (pid,r) and

if the output has more than log  tailing 0’s the party is added to the output set. By a simple Chernoff bound, the

size of the output set will be concentrated around t. The second sampler denoted by RandSet is the

straight-forward way to sample a random subset of t parties from

tailing 0’s the party is added to the output set. By a simple Chernoff bound, the

size of the output set will be concentrated around t. The second sampler denoted by RandSet is the

straight-forward way to sample a random subset of t parties from  without replacement: Order the parties

according to the output of h on input (pid,r) and select the ones with the highest value (where the output h is

taken as the standard binary representation of integers). It follows directly from the fact that h behaves as a random

oracle—and, therefore, assigns to each Pi ∈

without replacement: Order the parties

according to the output of h on input (pid,r) and select the ones with the highest value (where the output h is

taken as the standard binary representation of integers). It follows directly from the fact that h behaves as a random

oracle—and, therefore, assigns to each Pi ∈ a random number from {0,…,2k - 1}—that the above algorithm

uniformly samples a set ⊂

a random number from {0,…,2k - 1}—that the above algorithm

uniformly samples a set ⊂ of size t out of all the possible size-t subsets of

of size t out of all the possible size-t subsets of  . For completeness we have

included detailed description of both samplers in Appendix

A.2

. Given the above two samplers, we can

provide the formal description of our PoR-fair lottery, see Figure

6

. Theorem

1

states the achieved

security.

. For completeness we have

included detailed description of both samplers in Appendix

A.2

. Given the above two samplers, we can

provide the formal description of our PoR-fair lottery, see Figure

6

. Theorem

1

states the achieved

security.

|

|

|

|

L(

,Rep,c,δ,ϵ,r) ,Rep,c,δ,ϵ,r)

|

|

|

|

|

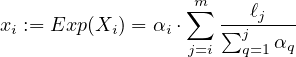

Theorem 1 (Reputation-Fair Lottery for m = O(1)-tiers). In the above lottery L( ,Rep,(c1,…,cm),δ,ϵ,r),

let ϵ,δ > 0 be strictly positive constants, and for each i ∈{1,…,m = O(1)}, let Xi be the random variable (r.v.)

corresponding to the number of parties in the final committee that are from set

,Rep,(c1,…,cm),δ,ϵ,r),

let ϵ,δ > 0 be strictly positive constants, and for each i ∈{1,…,m = O(1)}, let Xi be the random variable (r.v.)

corresponding to the number of parties in the final committee that are from set  i; and for each i ∈ [m] let

ci = max{c,c

i; and for each i ∈ [m] let

ci = max{c,c } where c = O(1) such that for some constant ξ ∈ (0,1) :

} where c = O(1) such that for some constant ξ ∈ (0,1) :  ≤

≤ -ξ. If for some constant

ϵf ∈ (0,1∕2) the reputation system Rep is ϵf-feasible for a static Rep-bounded adversary

-ξ. If for some constant

ϵf ∈ (0,1∕2) the reputation system Rep is ϵf-feasible for a static Rep-bounded adversary  , then for the set

, then for the set  sel of

parties selected by L the following properties hold with overwhelming probability (in the security parameter

k):

sel of

parties selected by L the following properties hold with overwhelming probability (in the security parameter

k):

The complete proof can be found in Appendix

C.1

. In the following we included a sketch of

the main proof

ideas.

Proof (sketch). We consider two cases: Case 1: L noes not reset, and Case 2: L resets.

In Case 1, The lottery is never reset. This case is the bulk of the proof.

First, in Lemma

3

using a combination of Chernoff bounds we prove that

the random variable Xi

corresponding to the number of parties from  i selected in the lottery is concentrated around the (expected)

value:

i selected in the lottery is concentrated around the (expected)

value:

|

(1) |

i.e., for any constant λi ∈ (0,1):

![Pr [|(1 - λi)xi ≤ Xi ≤ (1+ λi)xi] ≥ 1- μi(k),](main101x.png)

|

(2) |

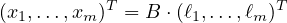

Hence, by inspection of the protocol one can verify that the xi’s and the ℓj’s satisfy the following system of linear equations:

|

(3) |

Where B is an m × m matrix with the (i,j) position being

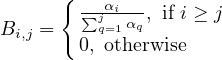

The above system of m equations has 2m unknowns. To solve it we add the following m equations which are derived from the desired reputation fairness: For each i ∈ [m - 1] :

|

(4) |

and

|

(5) |

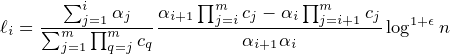

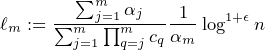

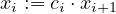

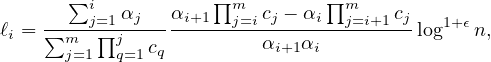

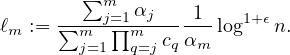

This yields 2m linear equations. By solving the above system of equations we can compute:

for each i ∈ [m - 1], and

This already explains some of the mystery around the seemingly complicated choice of the ℓi’s in the protocol. Next we observe that for each j ∈ [m] : ∑ i=1mBi,j = 1 which implies that

|

(6) |

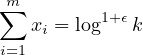

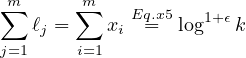

Because in each round we choose parties whose number is from a distribution centered around ℓi, the above implies that the sum of the parties we sample is centered around ∑ j=1mℓj = log 1+ϵk which proves Property 1.

Property 2 is proven by a delicate counting of the parties which are corrupted, using Chernoff bounds for bounding the number of corrupted parties selected by Rand (which selects with replacement) and Hoeffding’s inequality for bounding the number of parties selected by RandSet (which selects without replacement). The core idea of the argument is that because the reputation in different tiers reduces in a linear manner but the representation to the output of the lottery reduces in an exponential manner, even if the adversary corrupts for free all the selected parties from the lowest half reputation tiers, still the upper half will have a strong super-majority to compensate so that overall the majority is honest.

Finally, the c-fairness (Property 3) is argued as follows:

–The c-Representation Fairness follows directly from Equations

1

,

2

and

4

.

–The non-discrimination property follows from the fact that our lottery picks each party in every  i with exactly

the same probability as any other party.

i with exactly

the same probability as any other party.

–The c-Selection Fairness is proved by using the fact that the non-discrimination property

mandates that each party

in  sel ∩

sel ∩ i is selected with probability pi =

i is selected with probability pi =  . By using our counting of the sets’ cardinalities computed

above we can show that for any constant c′ < c:

. By using our counting of the sets’ cardinalities computed

above we can show that for any constant c′ < c:  ≥ c′.

≥ c′.

In Case 2 the lottery is reset and the output  sel is selected by means of invocation of algorithm Amax. This is

the simpler case since Lemma

1

ensures that if the reputation system is ϵf-feasible, then a fraction

1∕2 + ϵf of the parties in

sel is selected by means of invocation of algorithm Amax. This is

the simpler case since Lemma

1

ensures that if the reputation system is ϵf-feasible, then a fraction

1∕2 + ϵf of the parties in  sel will be honest except with negligible probability. Note that Amax is only

invoked if a reset occurs, i.e., if in some step there are no sufficiently many parties to select from;

this occurs only if any set

sel will be honest except with negligible probability. Note that Amax is only

invoked if a reset occurs, i.e., if in some step there are no sufficiently many parties to select from;

this occurs only if any set  i does not have sufficiently many parties to choose from. But the above

analysis, for δ < γ - 1, the sampling algorithms choose at most (1 + δ)log 1+ϵn with overwhelming

probability. Hence when each

i does not have sufficiently many parties to choose from. But the above

analysis, for δ < γ - 1, the sampling algorithms choose at most (1 + δ)log 1+ϵn with overwhelming

probability. Hence when each  i has size at least γ ⋅ log 1+ϵn, with overwhelming probability no reset

occurs. In this case, by inspection of the protocol one can verify that the number of selected parties is

|

i has size at least γ ⋅ log 1+ϵn, with overwhelming probability no reset

occurs. In this case, by inspection of the protocol one can verify that the number of selected parties is

| sel| = log 1+ϵn.

sel| = log 1+ϵn.

8 All our security statements here involve a negligible probability of error. For brevity we at times omit this from the statement.↩

9 The probability is taken over the coins associated with the distribution of the reputation system, and the coins of  and A.↩

and A.↩

10 This is analogous to the rankings of common reputation/recommendation systems, e.g., in Yelp, a party might have reputation represented by a number of stars from 0 to 5, along with their midpoints, i.e., 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, etc.↩

11 This also gives us a way to effectively remove a reputation party—e.g., in case it is publicly caught cheating.↩

13 In the random oracle model, r can be any unique nonce; however, for the epoch-resettable-adversary extension of our lottery we will need r to be a sufficiently fresh random value. Although most of our analysis here is in the static setting, we will still have r be such a random value to ensure compatibility with dynamic reputation.↩