C Deferred Proofs

C.1 Proof of Theorem 1

Proof. Without loss of generality we will assume that all ℓi’s above are integers, to avoid unnecessary rounding-related discussions. This assumption is without loss of generality as removing it might result in the samplers adding at most a constant number of parties on the sampled sets which will not change any of our asymptotic statement about the (relative) set sizes; furthermore, even if those additional parties are all corrupted, the asymptotic fraction of corrupted over honest parties will not change, since, as we prove, the sets are all super-constant with overwhelming probability and our corruption bound ensures that the adversary is far from the majority by an at least ϵδ fraction of the selected parties.

We consider two cases: Case 1: L noes not reset, and Case 2: L resets.

In Case 1 the output  sel is selected by means of invocation of algorithm Amax. Hence, by Lemma 1, if

the reputation system is ϵf-feasible, then a fraction 1∕2 + ϵf of the parties in

sel is selected by means of invocation of algorithm Amax. Hence, by Lemma 1, if

the reputation system is ϵf-feasible, then a fraction 1∕2 + ϵf of the parties in  sel will be honest except

with negligible probability. Note that in this case, the number of selected parties is |

sel will be honest except

with negligible probability. Note that in this case, the number of selected parties is | sel| = log 1+ϵn with

probability 1. Note that Amax is only invoked if a reset occurs, i.e., if in some step there are no

sufficiently

many parties to select from; this never occurs if every set

sel| = log 1+ϵn with

probability 1. Note that Amax is only invoked if a reset occurs, i.e., if in some step there are no

sufficiently

many parties to select from; this never occurs if every set  i has at least γ⋅log 1+ϵn and, therefore, c-fairness

does not apply in this case.

In Case 1, The lottery is never reset. This case is the bulk of the proof.

Conditioned on the lottery never

being reset to its default, we prove the following lemmas:

i has at least γ⋅log 1+ϵn and, therefore, c-fairness

does not apply in this case.

In Case 1, The lottery is never reset. This case is the bulk of the proof.

Conditioned on the lottery never

being reset to its default, we prove the following lemmas:

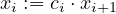

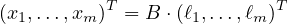

For each i ∈ [m] : let Xi denote the random variable corresponding to the number of parties from  i

selected in the lottery and let xi := Exp(Xi)

i

selected in the lottery and let xi := Exp(Xi)

Proof. Let  i = {

i = { i1,…,

i1,…, im

i}. For each

im

i}. For each  iρ ∈

iρ ∈ i and denote by χiρ,j the indicator random variable which

is 1 if

i and denote by χiρ,j the indicator random variable which

is 1 if  iρ is selected in the jth iteration of Step 4(b)i, i.e., if

iρ is selected in the jth iteration of Step 4(b)i, i.e., if  iρ ∈

iρ ∈ j, and 0 otherwise. The j-th iteration

of Step 4(b)i chooses every party in ∪q=1j

j, and 0 otherwise. The j-th iteration

of Step 4(b)i chooses every party in ∪q=1j q with probability

q with probability  independently of whether or not

any other party in ∪q=1j

independently of whether or not

any other party in ∪q=1j q is chosen. Indeed, observe that in the jth iteration of Step 4(b)i, the lottery L

samples always from the set ∪q=1j

q is chosen. Indeed, observe that in the jth iteration of Step 4(b)i, the lottery L

samples always from the set ∪q=1j q with replacement and conflicts are resolved later. Because, out of the

∑

q=1jαq parties in ∪q=1j

q with replacement and conflicts are resolved later. Because, out of the

∑

q=1jαq parties in ∪q=1j q, αi parties are from from

q, αi parties are from from  i, Pr[χiρ,j = 1] = αi

i, Pr[χiρ,j = 1] = αi independent of whether

or not any other party is chosen in

independent of whether

or not any other party is chosen in  j. Hence, each χiρ,j corresponds to a Bernoulli trial with the above

success probability and by application of the Chernoff bound for the r.v. Xi,j := ∑

ρ=1miχi

ρ,j corresponding

to the number of parties from

j. Hence, each χiρ,j corresponds to a Bernoulli trial with the above

success probability and by application of the Chernoff bound for the r.v. Xi,j := ∑

ρ=1miχi

ρ,j corresponding

to the number of parties from  i that are selected in Qj:

i that are selected in Qj:

|

(11) |

and for any λi,j ∈ (0,1) and some negligible function μi,j:

![Pr[|(1- λi,j)xi,j ≤ Xi,j ≤ (1+ λi,j)xi,j] ≥ 1- μi,j(k),](main203x.png) |

(12) |

Next we observe that although some of the parties in  j ∩

j ∩ i selected in Step 4(b)i might have been already

selected and included in

i selected in Step 4(b)i might have been already

selected and included in  sel (those are the parties in

sel (those are the parties in  coli,j), by selecting exactly |

coli,j), by selecting exactly | coli,j| parties without

replacement from

coli,j| parties without

replacement from  i, we ensure that the total number of parties selected in the jth iteration of Step 4(b) is exactly

Xi,j.

i, we ensure that the total number of parties selected in the jth iteration of Step 4(b) is exactly

Xi,j.

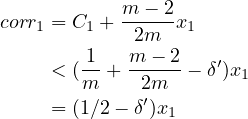

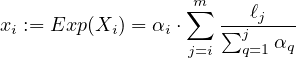

To complete the proof we observe that Xi = ∑ j=1mXi,j, hence by the linearity of expectation Equation 11 implies that

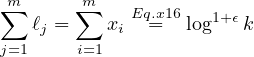

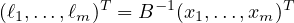

and Equation 12 implies that for any (λi,1,…,λi,m) ∈ (0,1)m

|

(13) |

for some negligible function μi (recall that constant-term sums and products of constantly many negligible functions are also negligible). Hence, by setting λi,j = λi∕m (recall that m = O(1) hence λi∕m is a constant) we derive the second property of the lemma.

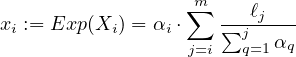

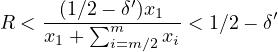

Given the above lemma, it is easy to verify that the xi’s and the ℓj’s satisfy the following system of linear equations:

|

(14) |

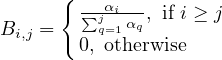

Where B is an m × m matrix with the (i,j) position being

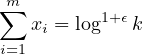

The above system of m equations has 2m unknowns. We add the following m equations:

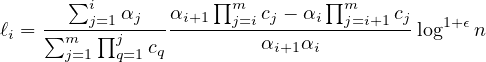

This yields 2m linear equations. By solving the above system of equations we can compute:

For each i = 1,…,m - 1:

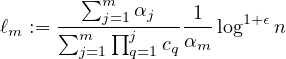

We next observe that for each j ∈ [m] : ∑ i=1mBi,j = 1 which implies that

|

(17) |

It is also easy to verify that B is invertible, hence

|

(18) |

We are now ready to prove properties 1 and 2 in the theorem. We start with Property 1:

Claim. With overwhelming probability (in the security parameter k) : | sel| = Θ(log 1+ϵn)

sel| = Θ(log 1+ϵn)

Proof. Let Lj denote the random variable corresponding to | j|, i.e., the total number of parties added to

j|, i.e., the total number of parties added to

sel in the jth iteration of Step 4. Lemma 2 implies that that for each

j ∈ [m]:

sel in the jth iteration of Step 4. Lemma 2 implies that that for each

j ∈ [m]:

|

(19) |

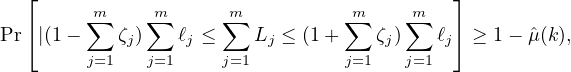

and for any constant ζj ∈ (0,1) and some negligible function  j:

j:

![Pr[|(1- ζj)ℓj ≤ Lj ≤ (1+ ζj)ℓj] ≥ 1 -μˆj(k),](main218x.png) |

(20) |

Let Psel denote the r.v. corresponding to the selected party set. By definition of the protocol: Psel := ∑ j=1mLj. Hence from the linearity of expectation and Equation 19 we have

Similarly, from Equation 20 we get

|

(21) |

for some negligible function  , which, for any given ζ, by setting each j ∈ [m] : ζj = ζ∕m, and

setting

, which, for any given ζ, by setting each j ∈ [m] : ζj = ζ∕m, and

setting  (⋅) = ∑

j=1m

(⋅) = ∑

j=1m (⋅) (which is also negligible when each

(⋅) (which is also negligible when each  j is negligible) and ∑

j=1mℓj = log 1+ϵk

derives

j is negligible) and ∑

j=1mℓj = log 1+ϵk

derives

![[ ]

Pr |(1 - ζ)log1+ϵk ≤ |Psel| ≤ (1 + ζ)log1+ϵk ≥ 1- ˆμ(k),](main225x.png) |

(22) |

which implies that with overwhelming probability |Psel| = Θ(log 1+ϵk).

We next proceed to Property 2:

Lemma 4. With overwhelming probability (in the security parameter k) for some constant ϵδ > 0 adversary

corrupts at most an 1∕2 - ϵδ fraction of the parties in

corrupts at most an 1∕2 - ϵδ fraction of the parties in  sel.

sel.

Proof. The reputation system Rep assigns to each party  i a reputation Ri ∈ [0,1] which corresponds to

the probability that

i a reputation Ri ∈ [0,1] which corresponds to

the probability that  i is honest. (Recall that we for this proof we consider static reputation

systems.) By

the independent reputations assumption, this probability is independent of whether or not any other party

in

i is honest. (Recall that we for this proof we consider static reputation

systems.) By

the independent reputations assumption, this probability is independent of whether or not any other party

in  becomes corrupted. This induces a probabilistic

adversary

becomes corrupted. This induces a probabilistic

adversary  who corrupts each reputation party

who corrupts each reputation party  i

independently with probability 1 - Ri. We wish to prove that this adversary corrupts at most a 1∕2 - ϵδ

fraction of the parties in

i

independently with probability 1 - Ri. We wish to prove that this adversary corrupts at most a 1∕2 - ϵδ

fraction of the parties in  sel. We will prove this by considering an adversary

sel. We will prove this by considering an adversary  ′ which is stronger than

′ which is stronger than  ,

i.e, where Pr[

,

i.e, where Pr[ ′ corrupts more than 1∕2 - ϵ parties in

′ corrupts more than 1∕2 - ϵ parties in  sel] ≥ Pr[

sel] ≥ Pr[ corrupts more than 1∕2 - ϵ parties in

corrupts more than 1∕2 - ϵ parties in

sel], and proving that this adversary

sel], and proving that this adversary  ′ corrupts more than 1∕2-ϵ parties with only negligible probability.

′ corrupts more than 1∕2-ϵ parties with only negligible probability.

Here is how  ′ is defined: For each

′ is defined: For each  i (recall that this includes parties with reputation between

(

i (recall that this includes parties with reputation between

( + δ,

+ δ, + δ]),

+ δ]),  ′ corrupts

′ corrupts  i with probability 1 - (

i with probability 1 - ( + δ). Note that for each party

+ δ). Note that for each party  ∈

∈ : Pr[

: Pr[ ′

corrupts

′

corrupts  ] ≥ Pr[

] ≥ Pr[ corrupts

corrupts  ] and this probabilities are independent of whether

] and this probabilities are independent of whether

′ (resp.

′ (resp.  ) corrupts any

other party. This ensures the above property between

) corrupts any

other party. This ensures the above property between  ′ and

′ and  . Hence, it suffices to prove the lemma for

. Hence, it suffices to prove the lemma for

′ which is what we do in the following.

′ which is what we do in the following.

Claim. In the ith iteration of Step 4, let Ci,j denote the random variable corresponding to the number of

corrupted parties in  i,j := (

i,j := ( i ∩

i ∩ j) ∪

j) ∪ i,j+, i.e., the number of parties from

i,j+, i.e., the number of parties from  j that are newly added to

j that are newly added to

sel and are corrupted by

sel and are corrupted by  ′. Then for some negligible function

μ for any constant 0 ≤ δ′ <

′. Then for some negligible function

μ for any constant 0 ≤ δ′ <  :

:

![m - i ′

Pr[Ci,j < (-m--- δ )|Qi,j|] > 1- μ(k).](main242x.png)

Proof. We consider three cases: Case 1:  coli,j = o(|

coli,j = o(| i,j|); Case 2:

i,j|); Case 2:  coli,j = ω(|

coli,j = ω(| i,j|); and Case 3:

i,j|); and Case 3:

coli,j = Θ(|

coli,j = Θ(| i,j|).

For Case 1: Since

i,j|).

For Case 1: Since  coli,j = o(|

coli,j = o(| i,j|), this implies that |(

i,j|), this implies that |( i∩

i∩ j)\j| = O(|

j)\j| = O(| i|). Hence Equation 20 implies

that with overwhelming probability |(

i|). Hence Equation 20 implies

that with overwhelming probability |( i∩

i∩ j)\j| = O(log 1+ϵk). However, since each party in

j)\j| = O(log 1+ϵk). However, since each party in  i is chosen

independently and the reputation is static, i.e., corruptions are defined before selecting the parties to

join

i is chosen

independently and the reputation is static, i.e., corruptions are defined before selecting the parties to

join

i, every party in (

i, every party in ( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j is corrupted by

j) \j is corrupted by  ′ with probability 1 - (

′ with probability 1 - ( + δ). But then an invocation

of the Chernoff bound yields that with overwhelming probability, for any δ′′ > 0 the fraction of corrupted

parties in (

+ δ). But then an invocation

of the Chernoff bound yields that with overwhelming probability, for any δ′′ > 0 the fraction of corrupted

parties in ( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j will be at most

j) \j will be at most  - δ + δ′′. Additionally since

- δ + δ′′. Additionally since  col

i,j = o(|

col

i,j = o(| i,j|), this implies

that for any constant δ′′′∈ (0,1) and for sufficiently large k |

i,j|), this implies

that for any constant δ′′′∈ (0,1) and for sufficiently large k | coli,j| < δ′′′|

coli,j| < δ′′′| i,j|. Hence, even if we allow

the adversary

i,j|. Hence, even if we allow

the adversary  ′ to corrupt all parties in

′ to corrupt all parties in  coli,j, for δ + δ′′′-δ′′ < ϵδ we will have that with overwhelming

probability the fraction of corrupted parties in

coli,j, for δ + δ′′′-δ′′ < ϵδ we will have that with overwhelming

probability the fraction of corrupted parties in  i,j will be at most

i,j will be at most  - ϵδ.

For Case 2: Since

- ϵδ.

For Case 2: Since  coli,j = ω(|

coli,j = ω(| i,j|), this implies that |

i,j|), this implies that | i,j+| = O(|Qi|). Hence Equation 20 implies that

with overwhelming probability |

i,j+| = O(|Qi|). Hence Equation 20 implies that

with overwhelming probability | i,j+| = O(log 1+ϵk). However, unlike the case above each party in

i,j+| = O(log 1+ϵk). However, unlike the case above each party in  i,j+

is not chosen independently, but rather a set of parties is chosen randomly. This corresponds to sampling

with replacement and we can no longe use the Chernoff bound. But since the reputation is static, i.e.,

corruptions are defined before selecting the above set, we can make direct use of Hoeffding's inequality [53]

(see Appendix D), to prove that with

overwhelming

probability, the fraction of corrupted parties in

i,j+

is not chosen independently, but rather a set of parties is chosen randomly. This corresponds to sampling

with replacement and we can no longe use the Chernoff bound. But since the reputation is static, i.e.,

corruptions are defined before selecting the above set, we can make direct use of Hoeffding's inequality [53]

(see Appendix D), to prove that with

overwhelming

probability, the fraction of corrupted parties in  i,j+

will be at most

i,j+

will be at most  - δ + δ′′. Additionally since

- δ + δ′′. Additionally since  col

i,j = ω(|

col

i,j = ω(| i,j|), this implies that for any constant

δ′′′∈ (0,1) and for sufficiently large k |(

i,j|), this implies that for any constant

δ′′′∈ (0,1) and for sufficiently large k |( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j| < δ′′′|

j) \j| < δ′′′| i,j|. Hence, even if we allow the adversary

i,j|. Hence, even if we allow the adversary

′ to corrupt all parties in (

′ to corrupt all parties in ( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j, for δ + δ′′′- δ′′ < ϵδ we again will have that with overwhelming

probability the fraction of corrupted parties in

j) \j, for δ + δ′′′- δ′′ < ϵδ we again will have that with overwhelming

probability the fraction of corrupted parties in  i,j will be at most

i,j will be at most  - ϵδ.

Finally in Case 3,

- ϵδ.

Finally in Case 3,  coli,j = Θ(|

coli,j = Θ(| i,j|) impies that |(

i,j|) impies that |( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j| = O(log 1+ϵk) and |

j) \j| = O(log 1+ϵk) and | i,j+| = O(log 1+ϵk).

Hence by using both arguments from the above two cases we can prove that (1) with overwhelming probability

the fraction of corrupted parties in (

i,j+| = O(log 1+ϵk).

Hence by using both arguments from the above two cases we can prove that (1) with overwhelming probability

the fraction of corrupted parties in ( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j will be at most (

j) \j will be at most ( -ϵδ∕2)|(

-ϵδ∕2)|( i ∩

i ∩ j) \j| and (2) with

overwhelming probability the fraction of corrupted parties in

j) \j| and (2) with

overwhelming probability the fraction of corrupted parties in  i,j+ will be at most (

i,j+ will be at most ( - ϵδ∕2) of the size

of Qj+. Therefore by a union bound, the fraction of corrupted parties in Qi,j will be at most

- ϵδ∕2) of the size

of Qj+. Therefore by a union bound, the fraction of corrupted parties in Qi,j will be at most  - ϵδ.

- ϵδ.

Next, we observe by inspection of the protocol that | i,j| = Xi,j. Since from for any constant λi,j > 0,

Equation 12 implies that

i,j| = Xi,j. Since from for any constant λi,j > 0,

Equation 12 implies that

![Pr[Xi,j ≤ (1 +λi,j)xi,j] ≥ 1- μˆi,j(k),](main260x.png)

i,j, and i,m, and λi,j are all constants, this implies that for any sufficiently small positive

constant δ′, and for some negligible function μi,j′:

i,j, and i,m, and λi,j are all constants, this implies that for any sufficiently small positive

constant δ′, and for some negligible function μi,j′:

![Pr[C < (m---i- δ′)x ] ≥ 1 - μ ′(k).

i,j m i,j i,j](main262x.png) |

(23) |

But then from a union bound we can deduce that there exists a negligible function  i such that:

i such that:

![Pr[∀j : C < (m--- i - δ′)x ] ≥ 1- ˜μ (k).

i,j m i,j i](main264x.png) |

(24) |

which implies that

![m m

∑ ∑ m---i ′ ′′

Pr[ Ci,j < ( m - δ )xi,j] ≥ 1 - μi(k),

j=1 j=1](main265x.png) |

(25) |

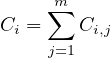

for some negligible μi′′. Denote by Ci the total number of corrupted parties from  i chosen in the lottery. By

inspection of the protocol:

i chosen in the lottery. By

inspection of the protocol:

Hence Equation 25 can be rewritten as follows

![Pr[C < (m--- i - δ′)x ] ≥ 1- μ′′(k)

i m i i](main268x.png) |

(26) |

Wlog assume that m is even (the case when m is odd is analogous):

For each i ∈{2,…,m∕2 - 1} the above implies that the majority of the parties in Ci is honest with overwhelming

probability. Hence, but a union bound, the majority of the parties in ∪i=2m∕2-1Qi is honest with overwhelming

probability. To complete the proof it suffices to prove that a (1∕2 -ϵδ′)-fraction of the parties in Q1 ∪ (∪j=m∕2mQj)

is honest with overwhelming probability. To this direction we observe that from Equation 26, with overwhelming

probability, Pr[C1 < ( - δ′)x1]. By an easy calculation, it follows that for any δ′ and any c such that∑

i=m∕2m

- δ′)x1]. By an easy calculation, it follows that for any δ′ and any c such that∑

i=m∕2m ≤

≤ - δ′ (which can be equivalently written as

- δ′ (which can be equivalently written as  ≤

≤ - δ′) the total number of

parties in ∪i=m∕2mQj is less than (

- δ′) the total number of

parties in ∪i=m∕2mQj is less than ( - δ′)x1. But if this is the case then then even if we allow the

adversary to corrupt all parties in every Qj (note that this is an even stronger adversary than

- δ′)x1. But if this is the case then then even if we allow the

adversary to corrupt all parties in every Qj (note that this is an even stronger adversary than  ′), still

with overwhelming probability the total number corr1 of corrupted parties in Q1 ∪ (∪i=m∕2mQj) will

be:

′), still

with overwhelming probability the total number corr1 of corrupted parties in Q1 ∪ (∪i=m∕2mQj) will

be:

|

(27) |

Hence with overwhelming probability, the fraction R of corrupted parties in Q1 ∪ (∪i=m∕2mQj) will be

|

(28) |

We next argue the following which will ensure that under Condition 2 of the

protocol, i.e., that every set

i has at least γ log 1+ϵn parties, with overwhelming probability the lottery never resets and hence

all the claims in this second case hold. This follows directly from the fact that the total number of

parties selected in the lottery will be less than γ log 1+ϵn with overwhelming probability; hence, none of

the invocation of Step 4 exceeds the size of the corresponding sets and therefore the lottery never

resets.

i has at least γ log 1+ϵn parties, with overwhelming probability the lottery never resets and hence

all the claims in this second case hold. This follows directly from the fact that the total number of

parties selected in the lottery will be less than γ log 1+ϵn with overwhelming probability; hence, none of

the invocation of Step 4 exceeds the size of the corresponding sets and therefore the lottery never

resets.

To complete the proof we show the c-fairness property of L in this case.

The c-Representation Fairness follows directly from Lemma 3 and Equation 15.

The non-discrimination property follows from the fact that our lottery picks each party in every  i with exactly the

same probability as any other party.

The c-Selection Fairness is proved as follows: Since by the non-discrimination

property every party has the same

probability of being picked, each party in each

i with exactly the

same probability as any other party.

The c-Selection Fairness is proved as follows: Since by the non-discrimination

property every party has the same

probability of being picked, each party in each  sel ∩

sel ∩ i is chosen with probability pi =

i is chosen with probability pi =  . However from

Lemma 3 we know that with overwhelming probability, for any

constant λi ∈ (0,1):

. However from

Lemma 3 we know that with overwhelming probability, for any

constant λi ∈ (0,1):

This means that with overwhelming probability, for all i = 1,…,m - 1:

|

(29) |

Where the last inequality follows by the definition of ci. For any constant c′ < c, by choosing λi and λi+1 such

that  ≥ c′∕c we can ensure that

≥ c′∕c we can ensure that  ≥ c′.

In Case 2 the lottery is reset and the output

≥ c′.

In Case 2 the lottery is reset and the output  sel is selected by means of invocation of algorithm Amax. This is

the simpler case since Lemma 1 ensures that if the reputation system is ϵf-feasible, then a fraction

1∕2 + ϵf of the parties in

sel is selected by means of invocation of algorithm Amax. This is

the simpler case since Lemma 1 ensures that if the reputation system is ϵf-feasible, then a fraction

1∕2 + ϵf of the parties in  sel will be honest except with negligible probability. Note that Amax is only

invoked if a reset occurs, i.e., if in some step there are no sufficiently many parties to select from; this

occurs only if any every set

sel will be honest except with negligible probability. Note that Amax is only

invoked if a reset occurs, i.e., if in some step there are no sufficiently many parties to select from; this

occurs only if any every set  i does not have sufficiently many parties to choose from. But the above

analysis, for δ < γ - 1, the sampling algorithms choose at most (1 + δ)log 1+ϵn with overwhelming

probability. Hence when each

i does not have sufficiently many parties to choose from. But the above

analysis, for δ < γ - 1, the sampling algorithms choose at most (1 + δ)log 1+ϵn with overwhelming

probability. Hence when each  i has size at least γ ⋅ log 1+ϵn, with overwhelming probability no reset

occurs. In this case, by inspection of the protocol one can verify that the number of selected parties is

|

i has size at least γ ⋅ log 1+ϵn, with overwhelming probability no reset

occurs. In this case, by inspection of the protocol one can verify that the number of selected parties is

| sel| = log 1+ϵn.

sel| = log 1+ϵn.

C.2 Proof of Theorem 2

Proof (sketch). Assume that every party has received the same genesis block. This block includes

the identifiers

(public keys) of all parties currently in  and their reputations (recall that for this proof, we assume

static

reputations) along with the randomness that seeds the lottery. Note that in the static adversary considered here,

this randomness is independent from the randomness that samples the corrupted set. Since

and their reputations (recall that for this proof, we assume

static

reputations) along with the randomness that seeds the lottery. Note that in the static adversary considered here,

this randomness is independent from the randomness that samples the corrupted set. Since  BA is selected by

means of L, and the lottery is ϵ-feasible, Theorem 1 ensures that the majority of

the parties in

BA is selected by

means of L, and the lottery is ϵ-feasible, Theorem 1 ensures that the majority of

the parties in  BA is honest.

This means that we can use a Byzantine broadcast protocol to have any party

BA is honest.

This means that we can use a Byzantine broadcast protocol to have any party  i ∈

i ∈ BA consistently

broadcast any messages to all the parties in

BA consistently

broadcast any messages to all the parties in  BA, i.e., in such a way that the following properties

hold:

BA, i.e., in such a way that the following properties

hold:

- (consistency) All partiers in

BA output the same message (string) Y as their output of the protocol

with sender

BA output the same message (string) Y as their output of the protocol

with sender  i.

i.

- (validity) If

i is honest, then Y is the string that

i is honest, then Y is the string that  i intended to broadcast (i.e., his input).

i intended to broadcast (i.e., his input).

Thus validity implies that for every honest  i ∈

i ∈ BC, if Ti is the set of valid transactions that

BC, if Ti is the set of valid transactions that  i has seen at round ρ,

then every (honest) party in

i has seen at round ρ,

then every (honest) party in  BA will output Ti along with a uniformly random string ri. Furthermore, by

consistency, we know that for every (honest or corrupted)

BA will output Ti along with a uniformly random string ri. Furthermore, by

consistency, we know that for every (honest or corrupted)  j the broadcast output with sender

j the broadcast output with sender  j is the same for

all parties in

j is the same for

all parties in  BA. Hence the union T of all transactions broadcasted by parties in

BA. Hence the union T of all transactions broadcasted by parties in  BC will be the same for all

BC will be the same for all  BA

members, and the same holds for the concatenation of all random nonces r broadcasted in the current round.

Additionally, because the history of the blockchain is the same for every party (in the first round this is the

genesis

block and in every subsequent round it is the sequence of the blocks until round ρ - 1), TH is the same for every

party in

BA

members, and the same holds for the concatenation of all random nonces r broadcasted in the current round.

Additionally, because the history of the blockchain is the same for every party (in the first round this is the

genesis

block and in every subsequent round it is the sequence of the blocks until round ρ - 1), TH is the same for every

party in  BA; hence every

BA; hence every  i ∈

i ∈ BA will compute the same Y =

BA will compute the same Y =  in Step 4 of the protocol. Consequently,

in Step 5, all honest parties in

in Step 4 of the protocol. Consequently,

in Step 5, all honest parties in  BA will sign the same (Y,h,ρ) and send it to the parties in

BA will sign the same (Y,h,ρ) and send it to the parties in  BC.

Since the majority of the parties in

BC.

Since the majority of the parties in  BA is honest, this implies that in Step 6, every party

in

BA is honest, this implies that in Step 6, every party

in  BC will

receive (Y,h,ρ) signed by at least the |

BC will

receive (Y,h,ρ) signed by at least the | BA|∕2 honest parties. Hence, if there is any honest party in

BA|∕2 honest parties. Hence, if there is any honest party in

BC the transaction pool T of that party broadcasted and included in

BC the transaction pool T of that party broadcasted and included in  and will be certifies by by

at least ⌈|

and will be certifies by by

at least ⌈| BA|∕2⌉ signatures from parties in

BA|∕2⌉ signatures from parties in  BA; this T will be adopted by all parties as the next

block, since, as we show below, the adversary is unable to make any party accept any other block.

Indeed, with overwhelming probability (i.e., unless the adversary forges an honest party’s signature) for

any (Y ′,h′,ρ′)≠(Y,h,ρ) the adversary will be able to produce at most ⌈|

BA; this T will be adopted by all parties as the next

block, since, as we show below, the adversary is unable to make any party accept any other block.

Indeed, with overwhelming probability (i.e., unless the adversary forges an honest party’s signature) for

any (Y ′,h′,ρ′)≠(Y,h,ρ) the adversary will be able to produce at most ⌈| BA|∕2⌉- 1 signatures on

(Y ′,h′,ρ′) from parties in

BA|∕2⌉- 1 signatures on

(Y ′,h′,ρ′) from parties in  BA. Hence the no value other than (Y,h,ρ) might be accepted by any

party.

BA. Hence the no value other than (Y,h,ρ) might be accepted by any

party.

![Pr[|(1- λi)xi ≤ Xi ≤ (1 + λi)xi] ≥ 1- μi(k),](main186x.png)